Everything You Wanted To Know About OA Of The Hip

I wrote a post a few years back about a mistake I made helping someone who had osteoporosis in their hip and how to avoid my mistake.

We’ve also been posting lots around different hip pathologies lately.

It can be confusing, to say the least, trying to determine exactly what is going on with a patient experiencing hip pain. Coming up with what we “think” is a diagnosis, then attempting to differentiate which pathology they are experiencing if there even is one.

Then, of course, using our clinical decision making to develop a treatment plan and homecare.

But, are we really sure we’re doing the right thing for each pathology?

Well since we’ve already done posts on the SI joint and Femoroacetabular Impingement, I figured it was time to take a look at the research on Osteoarthritis and what we can do to help.

Finding A Diagnosis

Yes, I know…we’re not allowed to diagnose.

But!, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have some knowledge around how this is diagnosed so we can better educate our patients on what they are dealing with.

OA of the hip is usually seen in middle-aged and elderly people, most often over the age of 601, with men having a higher prevalence.

It affects the joint capsule (as well as other structures around the joint) which in turn causes some muscle weakness and limits the range of motion1, mostly with internal rotation and flexion.

When we look at the clinical guidelines around OA of the hip1 there is a list of things used in the diagnosis:

- Moderate anterior or lateral hip pain during weight-bearing activities.

- Morning stiffness less than one hour in duration after waking.

- Hip internal rotation of less than 24°, or internal rotation and hip flexion 15° less than the non-painful side.

- Increased hip pain with passive internal rotation.

- Above the age of 50.

So if we are seeing someone and we suspect possible OA, or we are unsure of the diagnosis and their symptoms aren’t matching up to the above, this would be a good opportunity for us to refer out to get a possible differential diagnosis.1

Part of what we should assess is also what the daily function looks like for the patient sitting in front of us. What activities would they normally be doing that are being hindered because of the pain associated with this?

Also extremely important to take into account are: What are their goals? What are they hoping to get out of the treatment? What would a successful treatment look like to them?

The cited paper 1 gives four different activity tests which could be useful for you in your practice:

- 30 Second Chair Stand Test

- Seated on a chair, feet shoulder-width apart, arms crossed, patient stands up and repeats this as many times as possible for 30 seconds

- 4-Square Step Test

- Four canes placed with handles out at 90° angles to form four squares. The patient stands in square 1, steps forward with both feet into square 2, then steps right into square 3, then steps back into square 4. Sequence is then done in reverse and is timed.

- Step Test

- Patient steps on and off a 15cm step maintaining stance on the painful leg, both feet are placed on the step, then down to the floor on the opposite side. This is done for 15 seconds with the full number of steps counted.

- Timed Single Leg Stance

- The patient places hands on their hips and stands on the affected leg, with the knee of non-stance leg flexed so the foot is behind. The patient stands on 1 leg for as long as possible up to 30 seconds.

- Six Minute Walk Test 2

- You guessed it! Go for a walk with your patient. See how far they can go on a flat surface for 6 minutes in duration.

What I love about these assessments is how they all help to measure strength, balance, endurance, and flexibility…which are also the recommendations for exercise or homecare interventions for people with OA of the hip. So these could easily be part of homecare instructions to increase strength, balance, endurance, and flexibility and you can watch them all by clicking HERE.

In addition to these active assessments it is also important to document 1 flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER test) along with passive hip ROM and strength (which might be tough to do via special testing), which is where the above activities will help.

Now that you have an understanding of how individuals are diagnosed, and how we can do some assessment, it’s important to know what the research says on treatment.

The biggest recommendations are patient education, exercise, and manual therapy1.

Now, I’m not about to lecture you on the manual therapy end of things. You all have your favourite techniques and your patients come and see you because of what you do, so keep it up! When it comes to education, we aren’t so much educating patients on OA itself (we can leave that to the doctors and rheumatologists) but we can teach them some activity modifications and…you guessed it again…exercise. If the work you’re doing or if the guideline recommendations aren’t helping the patient see some improvement, this would also be a good time to refer out.

So let’s look at what the evidence says on exercise!

Exercise For Hip OA

Now it’s important to mention that weight loss is one of the main recommendations to help OA of the hip, however, counseling a patient on this is well out of our scope. Also, as Greg Lehman puts it, losing weight is really hard!

So let’s focus on what we can do (which in turn may help with a bit of weight loss), EXERCISE!

When reading over the research on this, the first statement that popped out to me was:

Pain is the dominant symptom although it is important to note that the severity of pain and the extent of changes on x-ray are not well correlated 3

This is crucially important as quite often people will get the x-ray to confirm a diagnosis and take this as an indication they shouldn’t exercise or can catastrophize over this, thinking they are so damaged exercise isn’t an option.

Pain along with joint stiffness, instability, swelling, and muscle weakness can lead to not only physical but psychological changes and impaired quality of life. 3 However, when we look at the benefits of exercise it can not only improve physical activities but can also help to improve a wide range of other functions including social, domestic, occupational, and recreation activities.

It can also help with fall risk, which is not only an immediate benefit but also a very long term benefit in preventing traumatic injuries due to fall accidents.

When looking at the type of exercise that would be most useful, it was determined that using supervised therapeutic exercise for strengthening the area is most beneficial and surprisingly (at least I was surprised) water-based exercise wasn’t as effective, nor was there as much research done in that area. Part of why this is not as effective is due to less of a load on the joint which does not correlate to walking ability or an increase in joint ROM. Also access to facilities is harder to come by compared to just being able to go for a walk outside.

However, it is suggested that for obese patients (I’m not about to make that assessment, this would be better coming from a doctor), or those who have more severe changes, aquatic exercise would probably be more beneficial until more load could be tolerated.

So, digging deeper into the research it goes back and forth as to what is more effective strengthening, or aerobic. However, the reason it seems to go back and forth is because it always comes down to what is most important, and or, more effective for the patient sitting in front of you. This way there is no “one” recommendation as far as exercise goes. To provide a good exercise recommendation is to look at what is affecting the patient more. Is it more important to strengthen the area according to the person’s daily needs? Or is aerobic exercise more important? What are the patients goals? Is going for a daily walk more important, or is being able to do a squat, climb a flight of stairs, or playing a game of tennis the top priorities.

I love these two quotes from our friend Bronnie Lennox Thompson:

Whatever the reason, tapping into that is more important than the form of the exercise.

and

Without some carryover into daily life (unless the exercise is intrinsically pleasurable), exercise is a waste of time.

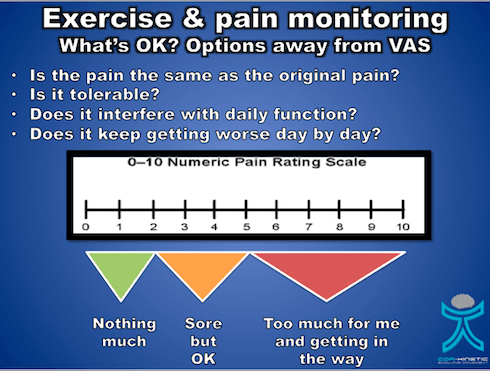

Now don’t get me wrong, exercise is never a waste of time and the evidence shows us, in this case, it can assist with daily function and help with pain (it will never completely get rid of pain). However, if we aren’t making the exercise applicable to, and enjoyable for the person, the likeliness they will do it is low. We also have to take into account they will likely have some discomfort with exercise but we must educate them on how this is not correlated to the condition getting worse. If we recommend an activity and 48 hours later there is some swelling, or the pain worsens this demonstrates that we have overdone it a bit and may have to back off the homecare dosage we have given them. We must use our clinical decision making not only in our dosage but also in what’s important to the person sitting in front of us.

References