Have We Ballsed Up The Biopsychosocial Model?

One of the most widely discussed topics in healthcare and especially in pain circles of late is the Bio Psycho Social model conceived by George Engel. The BioPsychoSocial (BPS) model was developed in reaction to the dominant biomedical viewpoint that involves reducing medicine to specific diseases or pathologies that can be identified and treated and this model forms the backbone of most western healthcare systems.

Engel felt the biomedical model:

“does not include the patient and his attributes as a person, a human being”

But the question is, have we misinterpreted the BioPsychoSocial model?

Are we simply applying it in the same way as the biomedical model it was trying to replace?

It’s People Not Just Pathology!

We know that people’s experiences of pain and pathology differ. The same painful problem may manifest as huge issue for one person disabling them from work and reducing dramatically their quality of life, whilst another person may remain relatively unaffected. This has to be taken into account both in treating the problem but also how the person is TREATED by their healthcare professional, their family and social network and the wider healthcare system.

We can see below from Engel’s view that it is a bi-directional model that involves the layers in which we exist rather than discreet treatment targets as we now see.

We could perhaps determine this interaction between layers as the wider impact OF the problem rather than just as impacting ON the problem. Rather than seeing the BPS as a direct treatment model where we dissect the three domains to find new pain ‘drivers’ to treat, the BPS perspective should really be seen as a CLINICAL philosophy and guide that can be used for improved patient care.Here is another interpretation from a recent paper ‘How do physiotherapists solicit and explore patients’ concerns in back pain consultations’

We could perhaps determine this interaction between layers as the wider impact OF the problem rather than just as impacting ON the problem. Rather than seeing the BPS as a direct treatment model where we dissect the three domains to find new pain ‘drivers’ to treat, the BPS perspective should really be seen as a CLINICAL philosophy and guide that can be used for improved patient care.Here is another interpretation from a recent paper ‘How do physiotherapists solicit and explore patients’ concerns in back pain consultations’

“underpinning the bps model is patient-centred care (pcc) which involves incorporating the patient’s perspective as part of the therapeutic process”

One of the issues that are often encountered in healthcare however is that clinicians AND patients want solutions and treatments rather than philosophies and the conversion into a treatment model conforms to the biomedical perspective that dominates healthcare.

Maybe the BPS asks us, as clinicians to better understand our patients and their subjective experience? And it may be better defined as a model of care rather than a model of treatment. Now, this does not mean we cannot involve a BPS thought process IN specific treatment but remember that this is just not really the major focus of the model, certainly as I understand it anyway.

So it is really treating people and their overall existence, not just treating their painful problems. These differing aspects cannot just be separated and simply targeted without an understanding of the person and the context they exist in, doing that for me is the biopsychosocial model in biomedical clothing.

Other commentators such as Leventhal have looked at concepts such as the disease and the illness *HERE*. The disease being the specific issue and the illness being the wider issues surrounding the problem, in my interpretation, this is similar in concept to the BPS. How is this PERSON individually affected by the problem that may even BECOME the problem itself?

Just Treat The Pain?

I can already hear some readers shouting, “Just treat the pain – then you will not have any more problems”

Well, that is the biomedical view in a nutshell!

Firstly we have been attempting to do this for ages, hence why there has been a call for a different model. Often treatments for pain are not successful and people need help in other ways and we treat pathology but pain persists. Perhaps the interaction with healthcare even makes the problem worse!

Can we treat the person and pain? Yes, I believe so. We should not forget this, just realize our limitations at doing so and also avoid pain being the only focus.

The question is do we often attempt to treat the person AND the pain? I don’t think this happens as much as we would care to admit. Maybe treating people rather than their pain can lead to reductions in pain? Maybe we cannot have an impact on people’s pain but affect suffering, disability, and quality of life? We may not be able to do this in a pain-focused model and why we end up with repetitive surgeries and the opioid epidemic?

People can still have pain and live a positive life; the BPS model is really well placed to help them do so and does life simply return to normal even after pain has reduced for all? I would hazard a guess that for many people their lives are fundamentally changed even AFTER persistent pain has decreased.

BPS Model Of Pain

A pain-oriented BPS model has emerged more recently and two examples of this can be found *here* and *here*. These interpretations should NOT be confused with Engel’s model I feel, and perhaps misses the essence of what he was reaching for. Maybe an issue with the BPS model is its breadth and how far-ranging it is? It is quite easy to place our interpretation anywhere within it.

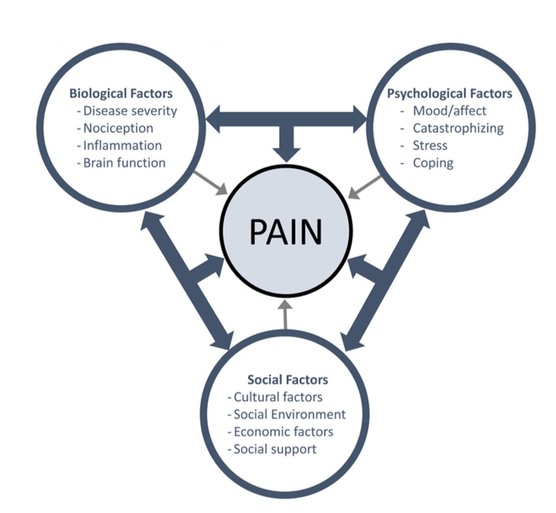

The pain focused model looks at how Biological Psychological and Social factors can influence pain.

This diagram is a great example with the arrows pointing solely inwards.

(Figure Fillingim 2017)

(Figure Fillingim 2017)“Pain is…..a process that emerges or unfolds through a whole person who is inseparable from the world”

but we should also consider the BPS perspective already to consider the whole world and our existence within it and not just its effect on pain!

The very essence of the BPS model was NOT to delve further and further into the microscopic components of biology but instead to also zoom out to encompass the other factors that may be at play in both pain and quality of life. I have written about this *HERE*. But if we consider most of the discussion, theories, and dominant messages around pain they focus on the reductionist view that Engel was trying to get away from.

As an example please insert any painful problem here ‘XXXXX’. Even the most uni-factorial biological one you can think of… let’s say a fracture.

How does their perception and knowledge, sense-making, around the issue affect them and their behaviors?

How does the injury affect their work and family life?

What are their perceived implications for the future?

How confident are they to return to sport or activity?

How motivated are they to engage in rehab or treatment?

This is considering the PERSON and heir engagement and embodiment in the world not just breaking down pain ‘drivers’ as the trend seems to have become and accusations of people forgetting the bio (eye roll).

Straight Lines & Trichotimies

Some of the criticisms of the BPS pain model focus on the division into three distinct components biological, psychological, and social as well as a perceived linear causality between the associated factors and pain.

My view of Engel’s work is that he objected to a linear causality model. Emergent properties such as pain NEVER have simple linear relationships with causes (whatever they are?). Again this is a misinterpretation and application specifically to pain of the original work. Linear causality is a criticism of previous Cartesian pain models but appears to be alive and well in the BPS.

The term ‘non-linear’ means that small things can give large effects but also large effects in one area may also give rise to no effects in the targeted area. There are so many interactions occurring that can affect each other that the same treatment may give rise to DIFFERENT positive or NEGATIVE outcomes dependent on the current state of the organism.

We seem to be happier for this to be the case now biomechanically, but less so biopsychosocially. If we are being honest then we have many more associations WITH pain from what is termed BPS factors than actual data from using these factors to treat pain.

The trend of splitting pain into separates categories of Biological, psychological, and social to diagnose and treat is another critique that Stilwell and Hartman highlight in their paper and neatly term a trichotomy. I feel Engel’s point was not that they exist distinctly as pathologies to treat but in their own right but to consider these things within the wider appreciation of the patient’s experience.

Conclusion

- We should really see the BPS model as a CLINICAL PHILOSOPHY and way of incorporating the patient into healthcare.

- It is intended to understand patients, their lives, and contexts.

- The biopsychosocial model COULD be used as a pain treatment model, but this is probably not how it was intended. This may be better termed a multi-dimensional pain treatment model.

- There is not really much data on outcomes from treatment using a BPS pain model.

- BPS factors are not simply linear treatment targets.

- We may need to better apply the BPS model rather than move beyond it.